The Inside Story of a Controversial New Text About Jesus

According to a top religion scholar, this 1,600-year-old text fragment suggests some early Christians believed Jesus was married—possibly to Mary Magdalene

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/mary-magdalene-discovery-631.jpg)

Editor's Note: In June 2016, reporter Ariel Sabar investigated the origins of the "Gospel of Jesus's Wife" for the Atlantic magazine. In response to Sabar's findings about the artifact's provenance, Harvard University scholar Karen King stated that the new information "tips the balance towards [the papryus being a] forgery."

Read the article that launched the controversy below.

In our November 2012 issue, writer Ariel Sabar reported from Rome on the reaction to King's discovery, both among the religious and academic communities. Read the full version of his report here.

Harvard Divinity School’s Andover Hall overlooks a quiet street some 15 minutes by foot from the bustle of Harvard Square. A Gothic tower of gray stone rises from its center, its parapet engraved with the icons of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. I had come to the school, in early September, to see Karen L. King, the Hollis professor of divinity, the oldest endowed chair in the United States and one of the most prestigious perches in religious studies. In two weeks, King was set to announce a discovery apt to send jolts through the world of biblical scholarship—and beyond.

King had given me an office number on the fifth floor, but the elevator had no “5” button. When I asked a janitor for directions, he looked at me sideways and said the building had no such floor. I found it eventually, by scaling a narrow flight of stairs that appeared to lead to the roof but opened instead on a garret-like room in the highest reaches of the tower.

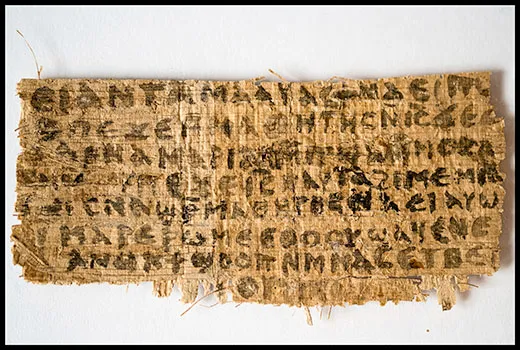

“So here it is,” King said. On her desk, next to an open can of Diet Dr Pepper promoting the movie The Avengers, was a scrap of papyrus pressed between two plates of plexiglass.

The fragment was a shade smaller than an ATM card, honey-hued and densely inked on both sides with faded black script. The writing, King told me, was in the ancient Egyptian language of Coptic, into which many early Christian texts were translated in the third and fourth centuries, when Alexandria vied with Rome as an incubator of Christian thought.

When she lifted the papyrus to her office’s arched window, sunlight seeped through in places where the reeds had worn thin. “It’s in pretty good shape,” she said. “I’m not going to look this good after 1,600 years.”

But neither the language nor the papyrus’ apparent age was particularly remarkable. What had captivated King when a private collector first e-mailed her images of the papyrus was a phrase at its center in which Jesus says “my wife.”

The fragment’s 33 words, scattered across 14 incomplete lines, leave a good deal to interpretation. But in King’s analysis, and as she argues in a forthcoming article in the Harvard Theological Review, the “wife” Jesus refers to is probably Mary Magdalene, and Jesus appears to be defending her against someone, perhaps one of the male disciples.

“She will be able to be my disciple,” Jesus replies. Then, two lines later, he says: “I dwell with her.”

The papyrus was a stunner: the first and only known text from antiquity to depict a married Jesus.

But Dan Brown fans, be warned: King makes no claim for its usefulness as biography. The text was probably composed in Greek a century or so after Jesus’ crucifixion, then copied into Coptic some two centuries later. As evidence that the real-life Jesus was married, the fragment is scarcely more dispositive than Brown’s controversial 2003 novel, The Da Vinci Code.

What it does seem to reveal is more subtle and complex: that some group of early Christians drew spiritual strength from portraying the man whose teachings they followed as having a wife. And not just any wife, but possibly Mary Magdalene, the most-mentioned woman in the New Testament besides Jesus’ mother.

The question the discovery raises, King told me, is, “Why is it that only the literature that said he was celibate survived? And all of the texts that showed he had an intimate relationship with Magdalene or is married didn’t survive? Is that 100 percent happenstance? Or is it because of the fact that celibacy becomes the ideal for Christianity?”

How this small fragment figures into longstanding Christian debates about marriage and sexuality is likely to be a subject of intense debate. Because chemical tests of its ink have not yet been run, the papyrus is also apt to be challenged on the basis of authenticity; King herself emphasizes that her theories about the text's significance are based on the assumption that the fragment is genuine, a question that has by no means been definitively settled. That her article's publication will be seen at least in part as a provocation is clear from the title King has given the text: “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.”

* * *

King, who is 58, wears rimless oval glasses and is partial to loose-fitting clothes in solid colors. Her gray-streaked hair is held in place with bobby pins. Nothing about her looks or manner is flashy.

“I’m a fundamentally shy person,” she told me over dinner in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in early September.

King moved to Harvard from Occidental College in 1997 and found herself on a fast track. In 2009, Harvard named her the Hollis professor of divinity, a 288-year-old post that had never before been held by a woman.

Her scholarship has been a kind of sustained critique of what she calls the “master story” of Christianity: a narrative that casts the canonical texts of the New Testament as divine revelation that passed through Jesus in “an unbroken chain” to the apostles and their successors—church fathers, ministers, priests and bishops who carried these truths into the present day.

According to this “myth of origins,” as she has called it, followers of Jesus who accepted the New Testament—chiefly the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, written roughly between A.D. 65 and A.D. 95, or at least 35 years after Jesus’ death—were true Christians. Followers of Jesus inspired by noncanonical gospels were heretics hornswoggled by the devil.

Until the last century, virtually everything scholars knew about these other gospels came from broadsides against them from early Church leaders. Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyon, France, pilloried them in A.D. 180 as “an abyss of madness and of blasphemy against Christ”—a “wicked art” practiced by people bent on “adapting the oracles of the Lord to their opinions.” (It’s a certainty that some critics will view “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” through much the same lens.)

The line between true believer and heretic hardened in the fourth century, when the Roman emperor Constantine converted to—and legalized—Christianity. To impose order on its factions, he summoned some 300 bishops to Nicaea. This council issued a statement of Christian doctrine, the Nicene creed, that affirmed a model of the faith still taken as orthodoxy.

In December 1945, an Arab farmer digging for fertilizer near the town of Nag Hammadi, in Upper Egypt, stumbled on a cache of manuscripts revealing the other side of Christianity’s “master story.” Inside a meter-tall clay jar containing 13 leatherbound papyrus codices were 52 texts that didn’t make it into the canon, including the gospel of Thomas, the gospel of Philip and the Secret Revelation of John.

As 20th-century scholars began translating the texts from Coptic, early Christians whose views had fallen out of favor—or were silenced—began speaking again, across the ages, in their own voices. A picture began to take shape of early Christians, scattered across the Eastern Mediterranean, who derived a multiplicity of sometimes contradictory teachings from the life of Jesus Christ. Was it possible that Judas was not a turncoat but a favored disciple? Did Christ’s body really rise, or just his soul? Was the crucifixion—and human suffering, more broadly—a prerequisite for salvation? Did one really have to accept Jesus to be saved, or did the Holy Spirit already reside within as part of one’s basic humanity?

Persecuted and often cut off from one another, communities of ancient Christians had very different answers to those questions. Only later did an organized Church sort those answers into the categories of orthodoxy and heresy. (Some scholars prefer the term “Gnostic” to heretical; King rejects both, arguing in her 2003 book, What is Gnosticism?, that “Gnosticism” is an artificial construct “invented in the early modern period to aid in defining the boundaries of normative Christianity.”)

One mystery that these new gospels threw new light on—and that came to preoccupy King—was the precise nature of Jesus’ relationship with Mary Magdalene. (King’s research on the subject preceded The Da Vinci Code, and made her a sought-after commentator after its publication.)

Magdalene is often listed first among the women who followed and “provided for” Jesus. When the other disciples flee the scene of Christ on the cross, Magdalene stays by his side. She is there at his burial and, in the Gospel of John, is the first person Jesus appears to after rising from the tomb. She is also, thus, the first to proclaim the “good news” of his resurrection to the other disciples—a role that in later tradition earns her the title “apostle to the apostles.”

In the scene at the tomb in John, Jesus says to her, “Do not cling to me, because I have not yet ascended…” But whether this touch reflected a spiritual bond or something more is left unstated.

Early Christian writings discovered over the past century, however, go further. The gospel of Philip, one of the Nag Hammadi texts, describes Mary Magdalene as a “companion” of Jesus “whom the Savior loved more than all the other disciples and [whom] he kissed often on the mouth.”

But scholars note that even language this seemingly straightforward is hobbled by ambiguity. The Greek word for “companion,” koinonos, does not necessarily imply a marital or sexual relationship, and the “kiss” may have been part of an early Christian initiation ritual.

In the early 2000s, King grew interested in another text, The gospel of Mary, which cast Magdalene in a still more central role, both as confidante and disciple. That papyrus codex, a fifth-century translation of a second-century Greek text, first surfaced in January 1896 on the Cairo antiquities market.

In the central scene of its surviving pages, Magdalene comforts the fearful disciples, saying that Jesus’ grace will “shelter” them as they preach the gospel. Peter here defers to Magdalene. “Sister, we know that the Savior loved you more than all the other women. Tell us the words of the Savior that you remember, the things which you know that we don’t because we haven’t heard them.’”

Magdalene relates a divine vision, but the other disciples grow suddenly disputatious. Andrew says he doesn’t believe her, dismissing the teachings she said she received as “strange ideas.” Peter seems downright jealous. “Did he then speak with a woman in private without our knowing it?” he says. “Are we to turn around and listen to her? Did he choose her over us?’” (In the Gnostic gospel of Thomas, Peter is similarly dismissive, saying, “Let Mary leave us, for women are not worthy of life.”)

As Jesus does in Thomas, Levi here comes to Magdalene’s defense. “If the Savior made her worthy, who are you then for your part to reject her?” Jesus had to be trusted, Levi says, because “he knew her completely.”

The gospel of Mary, then, is yet another text that hints at a singularly close bond. For King, though, its import was less Magdalene’s possibly carnal relationship with Jesus than her apostolic one. In her 2003 book The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle, King argues that the text is no less than a treatise on the qualifications for apostleship: What counted was not whether you were at the crucifixion or the resurrection, or whether you were a woman or a man. What counted was your firmness of character and how well you understood Jesus’ teachings.

“The message is clear: only those apostles who have attained the same level of spiritual development as Mary can be trusted to teach the true gospel,” King writes.

Whatever the truth of Jesus and Magdalene’s relationship, Pope Gregory the Great, in a series of homilies in 591, asserted that Magdalene was in fact both the unnamed sinful woman in Luke who anoints Jesus’ feet and an unnamed adulteress in John whose stoning Jesus forestalls. The conflation simultaneously diminished Magdalene and set the stage for 1,400 years of portrayals of her as a repentant whore, whose impurity stood in tidy contrast to the virginal Madonna.

It wasn’t until 1969 that the Vatican quietly disavowed Gregory’s composite Magdalene. All the same, efforts by King and her colleagues to reclaim the voices in these lost gospels have given fits to traditional scholars and believers, who view them as a perversion by identity politics of long-settled truth.

“Far from being the alternative voices of Jesus’ first followers, most of the lost gospels should rather be seen as the writings of much later dissidents who broke away from an already established orthodox church,” Philip Jenkins, now co-director of Baylor University’s Program on Historical Studies of Religion, wrote in his book Hidden Gospels: How the Search for Jesus Lost Its Way. “Despite its dubious sources and controversial methods, the new Jesus scholarship … gained such a following because it told a lay audience what it wanted to hear.”

Writing on Beliefnet.com in 2003, Kenneth L. Woodward, Newsweek’s longtime religion editor, argued that “Mary Magdalene has become a project for a certain kind of ideologically committed feminist scholarship.”

“Were I to write a story involving Mary Magdalene,” he wrote, “I think it would focus on this: that a small group of well-educated women decided to devote their careers to the pieces of Gnostic literature discovered in the last century, a find that promised a new academic specialty within the somewhat overtrodden field of Biblical studies.”

“Among these texts,” he continued, “The Gospel of Mary is paramount; it reads as if the author had obtained a DD degree from Harvard Divinity School.”

King didn’t hesitate to respond. Woodward’s piece was “more an expression of Woodward’s distaste for feminism than a review or even a critique of [the] scholarship,” she wrote on Beliefnet. “One criterion for good history is accounting for all the evidence and not marginalizing the parts one doesn’t like .... Whether or not communities of faith embrace or reject the teaching found in these newly discovered texts, Christians will better understand and responsibly engage their own tradition by attending to an accurate historical account of Christian beginnings.”

King is no wallflower in her professional life. “You don’t walk over her,” one of her former graduate students told me.

* * *

On July 9, 2010, during summer break, an e-mail from a stranger arrived in King’s Harvard in-box. Because of her prominence, she gets a steady trickle of what she calls “kooky” e-mails: a woman claiming to be Mary Magdalene, a man with a code he says unlocks the mysteries of the Bible.

This e-mail looked more serious, but King remained skeptical. The writer identified himself as a manuscript collector. He said he had come into the possession of a Gnostic gospel that appeared to contain an “argument” between Jesus and a disciple about Magdalene. Would she take a look at some photographs?

King replied that she needed more information: What was its date and provenance? The man responded the same day, saying he’d purchased it in 1997 from a German-American collector who acquired it in the 1960s in Communist East Germany. He sent along an electronic file of photographs and an unsigned translation with the bombshell phrase, “Jesus said this to them: My wife…” (King would refine the translation as “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife … ’”)

“My reaction is, This is highly likely to be a forgery,” King recalled of her first impressions. “That’s kind of what we have these days: Jesus’ tomb, James’s Ossuary.” She was referring to two recent “discoveries,” announced with great fanfare, that were later exposed as hoaxes or, at best, wishful thinking. “OK, Jesus married? I thought, Yeah, yeah, yeah.”

Even after reviewing the e-mailed photographs, “I was highly suspicious, you know, that the Harvard imprimatur was being asked to be put on something that then would be worth a lot of money,” she said. “I didn’t know who this individual was and I was busy working on other stuff, so I let it slide for quite a while.”

In late June 2011, nearly a year after his first e-mail, the collector gave her a nudge. “My problem right now is this,” he wrote in an e-mail King shared with me, after stripping out any identifying details. (The collector has requested, and King granted him, anonymity.) “A European manuscript dealer has offered a considerable amount for this fragment. It’s almost too good to be true.” The collector didn’t want the fragment to disappear in a private archive or collection “if it really is what we think it is,” he wrote. “Before letting this happen, I would like to either donate it to a reputable manuscript collection or wait at least until it is published, before I sell it.” Had she made any progress?

Four months later, after making a closer study of the photographs, she at last replied. The text was intriguing, but she could not proceed on photographs alone. She told the collector she would need an expert papyrologist to authenticate the fragment by hand, along with more details about its legal status and history.

William Stoneman, the director of Harvard’s Houghton Library, which houses manuscripts dating as far back as 3000 B.C., helped King with a set of forms that would permit Harvard to formally receive the fragment.

King brushed aside the collector’s offer to send it through the mail—“You don’t do that! You hardly want to send a letter in the mail!” So last December, he delivered it by hand.

“We signed the paperwork, had coffee and he left,” she recalls.

The collector knew nothing about the fragment’s discovery. It was part of a batch of Greek and Coptic papyri that he said he had purchased in the late 1990s from one H. U. Laukamp, of Berlin.

Among the papers the collector had sent King was a typed letter to Laukamp from July 1982 from Peter Munro. Munro was a prominent Egyptologist at the Free University Berlin and a longtime director of the Kestner Museum, in Hannover, for which he had acquired a spectacular, 3,000-year-old bust of Akhenaten. Laukamp had apparently consulted Munro about his papyri, and Munro wrote back that a colleague at the Free University, Gerhard Fecht, an expert on Egyptian languages and texts, had identified one of the Coptic papyri as a second-to fourth-century A.D. fragment of the Gospel of John.

The collector also left King an unsigned and undated handwritten note that appears to belong to the same 1982 correspondence—this one concerning a different gospel. “Professor Fecht believes that the small fragment, approximately 8 cm in size, is the sole example of a text in which Jesus uses direct speech with reference to having a wife. Fecht is of the opinion that this could be evidence for a possible marriage.”

When I asked King why neither Fecht nor Munro would have sought to publish so novel a discovery, she said, “People interested in Egyptology tend not to be interested in Christianity. They’re into Pharaonic stuff. They simply may not have been interested.”

Neither, necessarily, would have Laukamp. Manuscript dealers tend to worry most about financial value, and attitudes differ about whether publication helps or hinders.

King, however, could not ask. Laukamp died in 2001, Fecht in 2006 and Munro in 2008.

For legal purposes, however, the 1982 date of the correspondence was crucial, though it — along with the fact that Laukamp, Fecht and Munro were all dead — may well strike critics as suspiciously convenient. The next year, Egypt would revise its antiquities law to declare that all discoveries after 1983 were the unequivocal property of the Egyptian government.

Though King can read Coptic and has worked with papyrus manuscripts, she is by training a historian of religion. To authenticate the fragment, she would need outside help. A few weeks before the collector came to Harvard, King forwarded the photos to AnneMarie Luijendijk, a professor at Princeton and an authority on Coptic papyri and sacred scriptures. (King had overseen her doctoral dissertation at Harvard.)

Luijendijk took the images to Roger Bagnall, a renowned papyrologist who directs the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. Bagnall, who had previously chaired Columbia University’s department of classics, is known for his conservative assessments of the authenticity and date of ancient papyri.

Every few weeks, a group of eight to ten papyrologists in the New York area gather at Bagnall’s Upper West Side apartment to share and vet new discoveries. Bagnall serves tea, coffee and cookies, and projects images of papyri under discussion onto a screen in his living room.

After looking at the images of the papyrus, “we were unanimous in believing, yes, this was OK,” Bagnall told me when we spoke by phone.

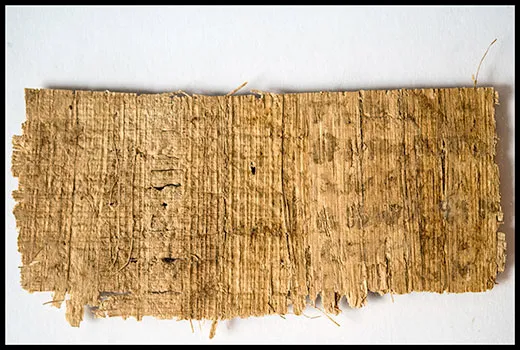

It wasn’t until King brought the actual fragment to Bagnall’s office last March, however, that he and Luijendijk reached a firm conclusion. The color and the texture of the papyrus, along with the parallel deterioration of the ink and the reeds, had none of the “tells” of a forgery. “Anyone who has spent any time in Egypt has seen a lot of fake papyrus, made of banana leaves and all sorts of stuff,” Bagnall told me.

Also convincing was the scribe’s middling penmanship. “It’s clear the pen wasn’t perhaps of ideal quality and the writer didn’t have complete control of it. The flow of ink was highly irregular. This wasn’t a high-class professional working with good tools. That is one of the things that tells you it’s real, because a modern scribe wouldn’t do that. You’d have to be really kind of perversely skilled to produce something like this as a fake.”

The Sahidic dialect of Coptic and the style of the handwriting, with letters whose tails do not stray above or below the line, reminded Luijendijk of texts from Nag Hammadi and elsewhere and helped her and Bagnall date the fragment to the second half of the fourth century A.D. and place its probable origins in Upper Egypt.

The fragment is some four centimeters tall and eight centimeters wide. Its rough edges suggest that it had been cut out of a larger manuscript; some dealers, keener on profit than preservation, will dice up texts for maximum return. The presence of writing on both sides convinced the scholars that it was part of a codex—or book—rather than a scroll.

In Luijendijk’s judgment, the scribe’s handwriting—proficient, but not refined—suggests that this gospel was read not in a church, where more elegant calligraphy prevailed, but among early Christians who gathered in homes for private study. “Something like a Bible study group,” Luijendijk told me.

“I had to not really let myself feel much excitement because of the disappointment factor—if it turns out to be a hoax or something,” King told me. “But once we realized what it was, then you get to start talking about the ‘Oh my’ factor.”

To help bring out letters whose ink had faded, King borrowed Bagnall’s infrared camera and used Photoshop to enhance the contrasts.

The papyrus’ back side, or verso, is so badly damaged that only a few key words—“my mother” and “three”—were decipherable. But on the front side, or recto, King gleaned eight fragmentary lines:

1) “not [to] me. My mother gave to me li[fe] … ”

2) The disciples said to Jesus, “

3) deny. Mary is worthy of it

4) ” Jesus said to them, “My wife

5) she will be able to be my disciple

6) Let wicked people swell up

7) As for me, I dwell with her in order to

8) an image

The line—“Jesus said to them, ‘My wife…’”—is truncated but unequivocal. But with so little surrounding text, what might it mean? Into what backdrop did it fit?

This is where King’s training as a historian of early Christianity came to bear.

Some of the phrases echoed, if distantly, passages in Luke, Matthew and the Gnostic gospels about the role of family in the life of disciples. The parallels convinced King that this gospel was originally composed, most likely in Greek, in the second century A.D., when such questions were a subject of lively theological discussion. (The term “gospel,” as King uses it in her analysis, is any early Christian writing that describes the life—or afterlife—of Jesus.) Despite the New Testament’s many Marys, King infers from a variety of clues and comparisons that the “Mary” in Line 3 is “probably” Magdalene, and that the “wife” in Line 4 and the “she” in Line 5 is this same Mary.

In the weeks leading up to the mid-September announcement, King worried that people would read the headlines and misconstrue her paper as an argument that the historical Jesus was married. But the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” was written too long after Jesus’ death to have any value as biography—a point King underscores in her forthcoming article in the Harvard Theological Review.

The New Testament is itself silent about Jesus’ marital status. For King, the best historical evidence that Mary was not Jesus wife is that the New Testament refers to her by her hometown, Migdal, a fishing village in Northern Israel, rather than by her relationship to the Messiah. “The most odd thing in the world is her standing next to Jesus and the New Testament identifying her by the place she comes from instead of her husband,” King told me. In that time, “women’s status was determined by the men to whom they were attached.” Think of “Mary, Mother of Jesus, Wife of Joseph.”

For King, the text on the papyrus fragment is something else: fresh evidence of the diversity of voices in early Christianity.

The first claims of Jesus' celibacy did not appear until about a century after his death. Clement of Alexandria, a theologian and Church father who lived from A.D. 150 to A.D. 215, reported on a group of second-century Christians “who say outright that marriage is fornication and teach that it was introduced by the devil. They proudly say that they are imitating the Lord who neither married or had any possession in this world, boasting that they understand the gospel better than anyone else.”

Clement himself took a less proscriptive view, writing that while celibacy and virginity were good for God’s elect, Christians could have sexual intercourse in marriage so long as it was without desire and only for procreation. Other early Church fathers, such as Tertullian and John Chrysostom, also invoked Jesus’ unmarried state to support celibacy. Complete unmarriedness —innuptus in totum, as Tertullian puts it—was how a holy man turned away from the world, and toward God’s new kingdom.

Though King makes no claims for the value of the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” as, well, a marriage certificate, she says it “puts into greater question the assumption that Jesus wasn’t married, which has equally no evidence,” she told me. It casts doubt “on the whole Catholic claim of a celibate priesthood based on Jesus’ celibacy. They always say, ‘This is the tradition, this is the tradition.’ Now we see that this alternative tradition has been silenced.”

“What this shows,” she continued, “is that there were early Christians for whom that was simply not the case, who could understand indeed that sexual union in marriage could be an imitation of God’s creativity and generativity and it could be spiritually proper and appropriate.”

In her paper, King speculates that the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” may have been tossed on the garbage heap not because the papyrus was worn or damaged, but “because the ideas it contained flowed so strongly against the ascetic currents of the tides in which Christian practices and understandings of marriage and sexual intercourse were surging.”

* * *

I first met King in early September at a restaurant on Beacon Street, a short walk from her office. When she arrived, looking a little frazzled, she apologized. “There was a crisis,” she said.

A little over an hour earlier, the Harvard Theological Review had informed her that a scholar who was asked to critique her draft had sharply questioned the papyrus’s authenticity. The scholar—whose name the Review doesn’t share with an author—thought that grammatical irregularities and the way the ink manifested on the page pointed to a forgery. Unlike Bagnall and Luijendijk, who had viewed the actual papyrus, the reviewer was working off low-resolution photographs.

“My first response was shock,” King told me.

After getting nods from Luijendijk, Bagnall and another anonymous peer reviewer, King had considered the question of authenticity settled. But the Review would not now publish unless she answered this latest criticism. If she could not do so soon, she told me, she would have to call off plans to announce the discovery, at an international conference on Coptic studies, in Rome. The date of her paper there, September 18, was just two weeks away.

Because of the fragment’s content, she had expected high-wattage scrutiny from other scholars. She and the owner had already agreed that the papyrus remain available at Harvard after publication for examination by other specialists—and for good reason. “The reflexive position will be, ‘Wait a minute. Come on.’ ”

Once the shock of the reviewer’s comments subsided, however, “my second response was, Let’s get this settled,” she told me. “I have zero interest in publishing anything that’s a forgery.”

Would she need 100 percent confidence? I asked.

“One-hundred percent doesn’t exist,” she told me. “But 50-50 doesn’t cut it.”

* * *

“Women, Sex and Gender in Ancient Christianity” met on the first floor of Andover Hall. It was a humid September afternoon and the class’s first day. So many students were filing in that King had to ask the latecomers to heft chairs in from a neighboring classroom.

“I can just sit on the floor,” volunteered a young woman in a pink tank-top and a necklace bearing a silver cross.

“Not for three hours,” King said.

She asked the students to introduce themselves and say why they’d signed up for the class.

“Roman Catholic feminist theology,” one student said of her interests.

“Monasticism,” said another.

“The sexualized language of repentance.”

“Queer theory, gender theory and gender performance in early Christianity.”

When the baton passed to the professor, she kept it simple; her reputation, it seemed, preceded her. “I’m Karen King,” she said. “I teach this stuff. I like it.”

Harvard established its divinity school in 1816 as the first—and still one of the few—nonsectarian theological schools in the country, and its pioneering, sometimes iconoclastic scholarship has made it an object of suspicion among orthodox religious institutions. Students come from a raft of religious backgrounds, including some 30 different Christian denominations; the largest single constituency, King said, is Roman Catholic women, whose Church denies them the priesthood.

For King, being on the outside looking in is a familiar vantage. She grew up in Sheridan, Montana, a cattle ranching town of 700 people an hour’s drive southeast of Butte. Her father was the town pharmacist, who made house calls at all hours of the night. Her mother took care of the children—King is the second of four—taught home economics at the high school and raised horses.

For reasons she still doesn’t quite understand—perhaps it was the large birthmark on her face, perhaps her bookishness—King told me that she was picked on and bullied “from grade school on.” For many years, she went with her family to Sheridan’s Methodist Church. In high school, however, King switched, on her own, to the Episcopal Church, which she regarded as “more earnest.”

“The Methodists were doing ’70s things—Coca-Cola for the Eucharist,” she told me. “I was a good student. I liked reading and ideas. It wasn’t that I was terribly righteous. But I didn’t like drinking, I didn’t like driving around in cars, I was not particularly interested in boys. And intellectually, the Episcopal Church was where the ideas were.”

After high school, she enrolled for a year at Western College, a small onetime women’s seminary in Ohio, before transferring to the University of Montana, where she abandoned a pre-med track after her religion electives proved more stimulating. A turning point was a class on Gnosticism, taught by John D. Turner, an authority on the Nag Hammadi discoveries.

At Brown University, where she earned her PhD, she wrote her dissertation on a Nag Hammadi manuscript called Allogones, or The Stranger. (She met her husband, Norman Cluley, a structural engineer, on a jogging path in Providence.)

Over dinner, I asked what had first drawn her to these so-called “heretical” texts. “I’ve always had a sense of not fitting in,” she told me. “I thought, if I could figure out these texts, I could figure out what was wrong with me.”

Was she still a practicing Christian? Her faith, she said, had sustained her through a life-threatening, three-year bout with cancer that went into full remission in 2008, after radiation and seven surgeries. She told me that she attends services, irregularly, at an Episcopal Church down the block from her home, in Arlington, a town northwest of Cambridge. “Religion is absolutely central to who I am in every way,” she said. “I spend most of my time on it. It’s how I structure my interior life. I use its materials when I think about ethics and politics.”

As for her career, however, “I never regretted choosing the university over church.”

* * *

When I spoke with Bagnall, the papyrologist, I asked whether he agreed with King’s reading of the “Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.” He said he found it convincing and appropriately cautious. Was there an Achilles’ heel? I asked. “The greatest weakness, I suppose, is that it is so fragmentary and it is far from being beyond the ingenuity of humankind to take this fragment and start restoring the lost text to say something quite different.”

Like King, he expects the fragment to inspire equal measures of curiosity and skepticism. “There will be people in the field of religious studies who say, ‘It’s Morton Smith all over again.’ ” Smith was a Columbia professor whose sensational discovery of a previously unknown letter by Clement of Alexandria didn’t stand up to scrutiny. Unlike King, though, Smith had only photographs of the alleged document, which had itself somehow vanished into thin air.

“Among serious scholars who work with this material, the reaction will likely be a lot of interest,” Bagnall said. “Outside the professional field, the reaction is likely to be”—he let out a short laugh—“less measured. I think there will be people upset, who will not have read the article and won’t understand just how measured and careful the treatment is.”

* * *

King had e-mailed the anonymous reviewer’s critique to Bagnall, and we were talking in her office when Bagnall’s reply arrived. She lifted her eyeglasses and leaned across the desk to look at the screen. “Ah, yeah, OK!” she said. “Go, Roger!”

What had he written? I asked.

“He’s saying he’s not persuaded” by the critique, “but nonetheless it would be good to strengthen the points the reviewer was raising.”

Four days later, King e-mailed me to say that her proposed revisions had satisfied the Review’s editors. She had shown the critical review to Bagnall, Luijendijk and Ariel Shisha-Halevy, an eminent Coptic linguist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who replied, “I believe—on the basis of language and grammar—the text is authentic.”

The scholars agreed with the reviewer’s suggestion that a noninvasive test—such as a spectrum analysis—be run to make sure the ink’s chemistry was compatible with inks from antiquity. But they were confident enough for her to go public in Rome, with the proviso that the results of the chemical analysis be added to her article before final publication.

She conceded to me the possibility that the ink tests could yet expose the piece as a forgery. More likely, she said, it “will be the cherry on the cake.”

King makes no secret of her approach to Christian history. “You’re talking to someone who’s trying to integrate a whole set of ‘heretical’ literature into the standard history,” she told me in our first phone conversation, noting later that “heretical” was a term she does not accept.

But what was she after, exactly? I asked. Was her goal to make Christianity a bigger tent? Was it to make clergy more tolerant of difference?

That wasn’t it. “I’m less interested in proselytizing or a bigger tent for its own sake than in issues of human flourishing,” she said. “What are the best conditions in which people live and flourish? It’s more the, How do we get along? What does it mean for living now?”

What role did history play? I asked. “What history can do is show that people have to take responsibility for what they activate out of their tradition. It’s not just a given thing one slavishly follows. You have to be accountable.”

As for “the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife,” “it will be big for different groups in different ways,” she said. “It will start a conversation. My thought is that that will be the longest real impact.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sabar_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Sabar_copy.jpg)